Introduction

Corrective feedback in the form of recasts has attracted considerable attention from SLA theorists and researchers and has also been investigated in a number of descriptive and experimental studies (for recent overviews, see Ellis & Sheen, 2006; Leeman, 2007; Nicholas, Lightbown, & Spada, 2001; Russell & Spada, 2006).Yet,whether and towhat extent recasts facilitate learning remains a controversial issue (e.g., Long, 2006; Lyster, 2007). Recasts are assumed to promote learners’ noticing of form while their primary focus remains on meaning/message. In this way, it is argued that recasts create an optimal condition for the cognitive comparison needed for learning to take place (Doughty, 2001; Long, 1996).

A. Recasts

Recasts constitute one kind of corrective feedback. They consist of target like reformulations of the errors that learners commit in the course of communicative activities. As noted earlier, they have been the subject of intense study by SLA researchers. For example, in the last decade alone (from 1997 to 2007), there have been more than 40 published studies that either investigated recasts in isolation or as one of several types of corrective feedback/interactional feed- back (see Ellis&Sheen, 2006; Leeman, 2007;Mackey, 2007; Russell & Spada, 2006, for a recent overview). There have also been a number of earlier studies, reviewed in Long (1996). The interest in recasts is due to the fact that they are of considerable theoretical interest to SLA researchers and also of pedagogical significance.

B. Uptake and Modified Output

Since Lyster and Ranta’s (1997) influential study documenting the different types of corrective feedback in an immersion classroom, the notion of learner “uptake” has attracted attention. Uptake is defined as “a student’s utterance that immediately follows the teacher’s feedback and that constitutes a reaction in some way to the teacher’s intention to draw attention to some aspect of the student’s initial utterance” (Lyster & Ranta, p. 49). In other words, a learner uptake move constitutes an attempt on the part of the learner to respond to the feedback. According to Lyster and Ranta, various learner responses can be classified as uptake (a) a simple acknowledgment, such as “‘yeah/ok/oh/yes,”(b) repetition of the original erroneous utterance, (c) repair by correcting the original error, and (d) partial repair (i.e., one part of the original utterance is repaired, but the rest is still in need of correction).

C. Language Anxiety

Language anxiety is considered one of the most important affective factors influencing the success of language learning (Horwitz, 2001). Questionnaire studies have found a significant negative lationship between anxiety and various L2 achievement measures such as final grades and oral proficiency tests (Horwitz & Young, 1991). Nevertheless, there is disagreement about the role played by language anxiety in learning. Language anxiety has been claimedto have a facilitating effect, a debilitating effect, and no effect at all on learners performance and L2 achievement (D¨ ornyei, 2005).

D. The Study

This study is part of a larger investigation (Sheen, 2006a) of the effect of corrective feedback in relation to individual difference factors. The two research questions that guided the current study are as follows:

1. Does language anxiety influence the effect that recasts have on the gram-matical accuracy of L2 learners’ English articles?

2. Is there a relationship between language anxiety and learners’ responses to recasts?

E. Design

The current study employed a quasi-experimental classroom study. Out of four intact classes, four groups (two experimental and two controls) were formed.

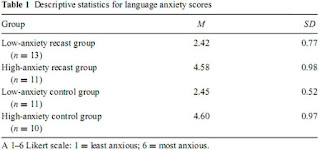

Based on their responses to a language anxiety questionnaire, the learners in the four classes were classified as having low or high anxiety using the total mean score (M = 3.36) and standard deviation (SD = 1.01) for the whole sample (N = 61). Learners who scored more than one standard deviation above.

The mean were classified as “high-anxiety” and learners who scored more than one standard deviation below were classified as “low-anxiety.” Those learners (N = 14) whose score fell within one standard deviation of the mean were not included in the analysis. Two additional learners (who did not complete the delayed posttests) were also excluded from the final study, resulting in a total of 45 students in the high- and low-anxiety groups. As a result, the following four groups were distinguished within the intact classes: a high-anxiety recast the mean were classified as “high-anxiety” and learners who scored more than one standard deviation below were classified as “low-anxiety.” Those learners (N = 14) whose score fell within one standard deviation of the mean were not included in the analysis. Two additional learners (who did not complete the delayed posttests) were also excluded from the final study, resulting in a total of 45 students in the high- and low-anxiety groups. As a result, the following four groups were distinguished within the intact classes: a high-anxiety recast group (N = 13); a low-anxiety recast group (N = 11); a high-anxiety control group (N = 11); and a low-anxiety control group (N = 10). Neither of the two control groups completed the narrative tasks or received recasts (i.e., they only completed the tests).

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for the language anxiety scores of the four groups. The questionnaire used to measure language anxiety is described below. The mean scores for the four groups ranged from 2.55 (least anxious) to 4.60 (most anxious) on a 6-point scale. Aone-way ANOVA revealed that these differences were statistically significant, F(3, 41) = 3.62, p < .05; the significant pair wise contrasts lay between (a) low- and high-anxiety recast groups, (b) low- and high-anxiety control groups, and (c) low-anxiety recast and high-anxiety control groups, and (d) high-anxiety recast and low-anxiety control group. During the 2weeks prior to the start of the recast treatment, the participating students signed consent forms and completed a background questionnaire. In the following week, they completed the pretests. Then the two treatment sessions took place in the next 2weeks. The immediate post tests were completed on the same day as the second treatment session and the delayed posttests 4 weeks later. During each testing session, three tests were administered in.

F. Participants

The participants came from a large ESL program in a community college in the United States. They were four native-speaking American teachers and 61 students who were placed in the intermediate proficiency level classes (level II, with level IV the most advanced). Students were drawn from both international and immigrant ESL populations and varied greatly in terms of age (ranging from 21 to 55 years of age), linguistic background (representing seven different first languages [L1s]), and ethnic and educational background (ranging from high school diplomas to MA/law/medical degrees). The demographic details. of the participants are as follows: male, 15; female, 46; Spanish, 18; Polish, 9; Korean, 12; Japanese, 1; Chinese, 2; Russian, 2; Turkish, 3; and others or multiple L1s, 14; college degree or higher, 33; others, 28; less than a year of residence in the United States, 11; a year or higher, 50. Class sizes ranged from 12 to 16. Only the 45 students who completed the language anxiety questionnaire, the pretest, and the two post tests (immediate and delayed) and who had pretest scores lower than 75%2 were finally included in the study.

COMMENT

INTRODUCTION

Learning language is an important activity in our life moreover learning English which has been an international language. Measuring how far the successfulness of learning language is can be measured from all skills or output that the learners have. They should be master all parts of language that they learn then apply it in their daily life.

How far the learners can accept all materials that they learn supported by some factors such kind of environment, teacher, material, etc. learning process also need a good environment to make the learners feel comfort in that process. In the other hand, teacher as the leader in the classroom should give a good things to all learners from all sides of teaching and learning process. They are teaching media, technique, etc.

In learning language process, error of learning is always happen. They will try many kinds of activity along of study. So, the teacher should analyze of that activity to define the error of language learning, then he or she can decide which error should me overcame.

To discuss that case above, in this study the researcher take a title recasts, language anxiety, modified output, and l2 learning.

a. Recast

Recasts are among the most frequently studied types of corrective feedback. Despite their popularity, however, researchers have failed to reach a consensus regarding how to operationally define them uniformly in different contexts. Table 1 adapted from Ellis and Sheen (2006) provides an overview of operational definitions of recasts in several studies. One reason why recasts have been the focus of study by many researchers is that recasts are one of the most frequently used feedback types in L2 classrooms (Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Panova & Lyster, 2002; Sheen, 2004). Lyster (1998a), for example, examining the distribution of six types of corrective feedback in four immersion classrooms in Canada found that recasts were the most frequent type of corrective feedback used by teachers. Similarly, Sheen (2004) examining the distribution of recasts in four communicative setting (French immersion, Canada ESL, New Zealand ESL , and Korea EFL) found that, on average, 60% of all the feedback moves involved recasts. Furthermore, recasts have been considered as an appropriate and ideal corrective move because they provide learners with opportunities to focus on form without disrupting the flow of communication. Trofimovich, Ammar, and Gatbonton (2007) stated that recasts are ideal interactional feedback moves because they are implicit and unobtrusive (i.e. they highlight the error without breaking the flow of communication) and are also learner-centered (i.e. they are contingent on what the learner is trying to communicate). Despite the frequency of recasts in L2 classrooms, their saliency to learners as corrective moves has been questioned by some researchers on the ground that some learners may fail to distinguish them from non-corrective repletion of learners’ utterances which are used as confirmation of the message. The following example adapted from Nicholas, Lightbown, & Spada (2001) displays how recasts can play two functions simultaneously and thus remain ambiguous to learners: S: The boy have many flowers in the basket. T: Yes, the boy has many flowers in the basket. (Nicholas et al, 2001, p. 721) In the above example, the recast serves two functions simultaneously. Conversationally, it helps communication keep going and provides a confirmation to the student utterance, and as a corrective feedback, it provides an indication to the student that an incorrect form has been produced. Such a functional ambiguity compels some researchers to argue against the effectiveness of recasts as corrective feedback.

b. Language anxiety

Recasts are among the most frequently studied types of corrective feedback. Despite their popularity, however, researchers have failed to reach a consensus regarding how to operationally define them uniformly in different contexts. Table 1 adapted from Ellis and Sheen (2006) provides an overview of operational definitions of recasts in several studies. One reason why recasts have been the focus of study by many researchers is that recasts are one of the most frequently used feedback types in L2 classrooms (Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Panova & Lyster, 2002; Sheen, 2004). Lyster (1998a), for example, examining the distribution of six types of corrective feedback in four immersion classrooms in Canada found that recasts were the most frequent type of corrective feedback used by teachers. Similarly, Sheen (2004) examining the distribution of recasts in four communicative setting (French immersion, Canada ESL, New Zealand ESL , and Korea EFL) found that, on average, 60% of all the feedback moves involved recasts. Furthermore, recasts have been considered as an appropriate and ideal corrective move because they provide learners with opportunities to focus on form without disrupting the flow of communication. Trofimovich, Ammar, and Gatbonton (2007) stated that recasts are ideal interactional feedback moves because they are implicit and unobtrusive (i.e. they highlight the error without breaking the flow of communication) and are also learner-centered (i.e. they are contingent on what the learner is trying to communicate). Despite the frequency of recasts in L2 classrooms, their saliency to learners as corrective moves has been questioned by some researchers on the ground that some learners may fail to distinguish them from non-corrective repletion of learners’ utterances which are used as confirmation of the message. The following example adapted from Nicholas, Lightbown, & Spada (2001) displays how recasts can play two functions simultaneously and thus remain ambiguous to learners: S: The boy have many flowers in the basket. T: Yes, the boy has many flowers in the basket. (Nicholas et al, 2001, p. 721) In the above example, the recast serves two functions simultaneously. Conversationally, it helps communication keep going and provides a confirmation to the student utterance, and as a corrective feedback, it provides an indication to the student that an incorrect form has been produced. Such a functional ambiguity compels some researchers to argue against the effectiveness of recasts as corrective feedback.

In learning language as L2, the teachers and the students should pay attention of all parts of it. Realizing the goal of language learning is for having communication in daily life, so all activities should support of that main goal. The teacher also should pay attention of students’ activity especially of students’ error. She or he is forbidden to blame that his or her students are wrong, but they should analyze how can it be, and how to solve that error. The teacher should give a good motivation for the students to learn more and overcome that problem.

Finally, that this journal is important enough for the teacher as the leader of classroom to identify the learning activity that happen. So, it can support the teachers to improve their learning activity to make the classroom problem can be overcame.